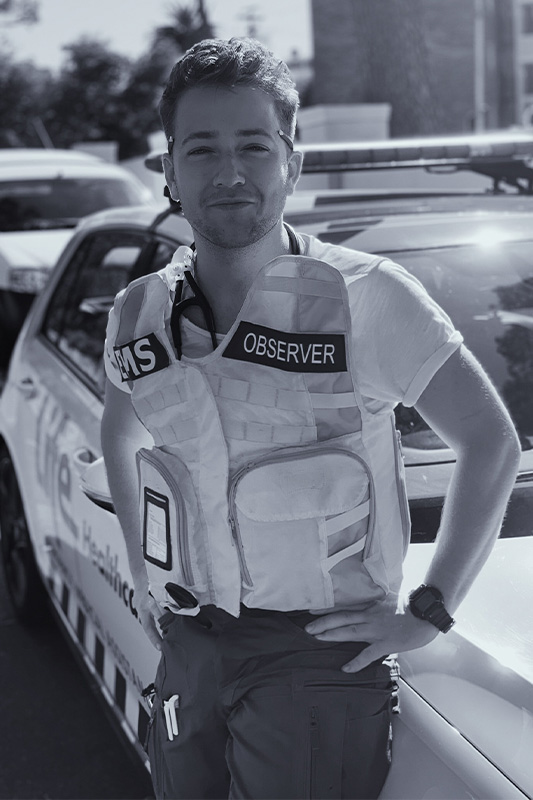

In early 2020, when the Covid pandemic seemed as far away as the Cape of Good Hope is from the imperial palace of the Habsburg dynasty, Daniel Knogler was interning as a paramedic in Cape Town. The excellently trained local emergency personnel left a lasting impression on the Viennese doctor. Now, in 2022, the thirty-year-old is back at the southern tip of the African continent for another year – this time, in pandemic conditions and with a brand-new team.

A first responder on Tour

Has the coronavirus changed the situation? “Not in terms of the calls we get,” Daniel explains, “except when it comes to masks.” South Africans, he says, are extremely disciplined in wearing them, even though the virus is absolutely everywhere. Be it on duty or in daily life, even the smallest store has an attendant at the door splashing sanitizer on the hands of everyone who seeks entrance. “If you don’t open your hands, you won’t get in,” the Austrian continues. “No noses are poking out of masks anywhere.”

Cape Town’s emergency care practitioners (ECPs) face tough situations. Every day, they deal with gunshot wounds, stab wounds and severe traumas following fights or car crashes. “There was a thirteen-year-old with a gunshot wound to the head…”, Daniel recalls. “We were the first responders, so we were able to administer the general anesthesia. Three days later, the boy was dead. These things stay with you.”

Mass-casualty Incident

Of course, there are always bad apples, he says. This goes for his profession, too. Some emergency responders base their sense of importance on the number of intubations they perform. One of his colleagues on the streets of Cape Town genuinely impressed him with her exemplary empathy, however: the scene was a full frontal collision in Blouberg, around the corner from the worldclass surfing beach. An almost full coach had hit a car, 29 people injured, three dead. “Sometimes, being there for a patient on the worst day of their life and giving them back some sense of inner peace by providing good care is more important than simply ramming a tube down their throat,” she later explained to him.

She also told him a story about Uber, the taxi app. In South Africa, the police virtually never stop cars to perform a breathalyzer test, and the locals are rather cavalier about driving drunk. This often leads to accidents with injuries that are barely imaginable from a European perspective. When Uber came to Cape Town, the number of accidents under the influence of alcohol notably fell. “That’s the good part,” Daniel says. The downside was competition with the established taxi drivers, some of whom are members of criminal organizations. “It’s not unusual for them to ambush and shoot Uber drivers.” Some townships have become completely off limits for Uber drivers. Incredible. “It’s usually already too late when we arrive to such a scene.”

One time, when the emergency responders were called to an apartment whose owner had had a heart attack, their intubation and reanimation efforts fell flat. “After trying for fifteen minutes, we had to abort – with all the family watching,” Daniel remembers. Once the death certificate had been issued and the paramedics were packing up their equipment, the relatives broke into rhythmic chanting, clapping their hands. “To me, it was an unfamiliar way of coping with grief, completely different to our culture,” Daniel describes the scene. “But there was something captivatingly beautiful about it.”

The team take a short break at a gas station. Most are open around the clock, offering small bars “serving genuinelygood coffee,” as Daniel tells us with more than a little appreciation. Back in Vienna, he really misses the nightly pickme-up. Recalling one particular coffee break, he continues: “We’d just got the first sip of cappuccino in when a call came in. Two “red patients” with multiple gunshot wounds to the chest. Daniel and his Austrian colleague, who had studied medicine in Graz and accompanied him to South Africa, were the first to arrive on the scene along with the ECP. Having provided first aid, assessed the situation, administered medication and inserted a chest tube, the ambulance arrives. A bench that normally seats the ECPs inside the vehicle is converted into a fully functional stretcher. Transporting two patients in a highly critical condition in an ambulance and showing up unannounced in a shock room with them is completely normal in Cape Town. “Unimaginable back home,” Daniel comments, visibly impressed. He points out another significant difference: instead of using the NACA score, a system for assessing the severity of an injury or illness that is widely used in Europe, patients in the South African metropolis are color-coded. Red: acute threat to life Orange: possible threat to life Yellow: inpatient treatment. Green: mild injury or illness Blue: deceased.

Manholes an Skills Lab

All these things are taught in the Department of Emergency Medicine of the Cape Peninsula University of Technology, the main training institution for emergency doctors at the Cape. On campus, there are deep manholes for rope rescue training, large pools for practicing water rescue, and a special Skills Lab that can realistically simulate any kind of scenario. Not only are ECPs taught about pre-clinical medicine, i.e., first-response care on the site of an accident, they also learn to handle emergencies at hospitals. The Department’s graduates are highly qualified medical practitioners whose training has prepared them for virtually any scenario. It is a level of education “that many European countries would be well advised to emulate,” Daniel enthuses. “Quite a few of our own emergency doctors could take a leaf out of the South African ECPs’ book.”

An internship in cape town

When Daniel submitted his request for leave, Cape Town still was on emergency level 6, the highest possible level of alert. Things had calmed down markedly by the time he arrived to start his internship. Despite the lowered alert level, Daniel cannot help but notice the Capetonians’ “remarkable discipline” when it comes to pandemic safety. Again, the four weeks spent looking over his South African colleagues’ shoulders left him with lasting impressions – and no infection. But only two weeks after his return to Vienna, during his first foray into the city’s nightlife, the virus finally caught up with him. For nearly a whole week, he had a fever of almost 104°F. Covid can get you anywhere. In that respect, Daniel comments with a smirk, Vienna can be more dangerous than Cape Town if you aren’t careful.