A cellar full of horned beasts and grotesque grimaces. Markus Spiegel is the creator of these terrifying creatures. Through his work, he breathes life into wood and preserves an ancient tradition.

A skull watches over the workbench from above. A pile of sawdust has accumulated on top of it. Markus has glued two pieces of wood together and is in the process of screwing a metal plate onto them. Now, he holds the pieces in place with a vise. With his chainsaw, he trims the wooden block. Sawdust fills the air. Gradually, we can make out the shapes of a nose, forehead and chin. This blank will soon be transformed into a frightening grimace.

Perchta vs. Krampus

Perchta are mythical figures from Bavarian and Austrian folklore. Draped in shaggy animal furs, they carry heavy bells and hide their face behind a carved mask made of pinewood. Around the new year, they roam towns and villages in large groups, chasing away the old year, winter, and evil spirits. The centuries-old custom probably has its roots in pagan rituals. Krampuses are similar in appearance but have a different background story. Krampus (or Bartl) is the assistant of Saint Nicholas, and his job is to punish children who have been naughty throughout the year.

Homemade Horrors

“When I was a little boy, around ten or twelve, my friends and I wanted to play Krampus,” Markus recounts. They made cardboard masks to startle passers-by at night. But their fear of Krampus himself was much greater than their courage. As the boys grew up, so did their fascination with the legend. But Markus was not happy with the masks on offer. “You either had to travel half the world to find a mask or pay through your nose,” he explains. Twenty years ago, he took matters into his own hands. With a wooden block and a chisel, he started carving his own masks in his living room.

In the beginning, Markus was the only one who wore the masks, but over time, he was approached by more and more friends and colleagues. Demand grew, and Markus turned his hobby into a business. “I was able to make a good living off of it until the pandemic,” he tells us. Thankfully, he spotted a vacancy advertised by the professional fire brigade at that time and got the job. His shifts leave him enough time for wood carving. “The Krampus processions have returned, so my business is sure to recover, too.”

Raising the dead

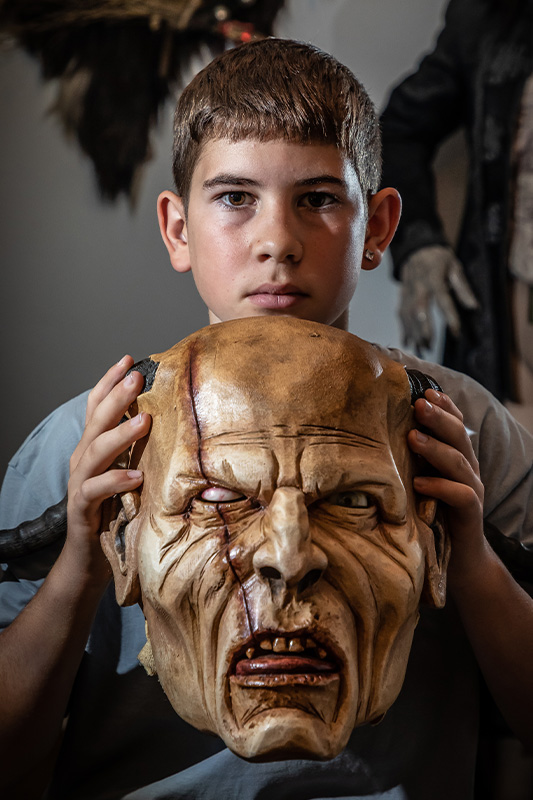

Markus is standing in front of his workbench. The wall is covered in chisels of varying shapes and angles. He picks the right tool, puts it to the wood and leans his upper body forward to run the chisel along the contours. “I’d rather use my own strength than the clapper,” he explains. His approach is more tiring, but it allows him to work much more carefully. Not that the blank would care, mind you. Markus is working on a group of figures inspired by the TV series “The Walking Dead.” The zombie’s head in his vise has a wide-open mouth and pointy teeth, deep wrinkles, protruding cheekbones and not much of a nose. With a thin, bent piece of iron, Markus scrapes holes into the chin, forehead and cheeks. It took less than two hours for this frightening face to emerge from the wooden block.

But the undead creature is still waiting for his companions. “First, I carve the whole group. Then I hollow them out, give them horns and paint everything,” explains Markus. He does everything by himself, from the first step to the final touches. When we ask him how many masks he has carved since the start of his creative endeavor, he cannot give us an answer. Quite a few ended up in the fire, especially in the beginning. They vary in price, too, depending on the difficulty of a project and the cost of the horns. “Some horns, like those of a Marco Polo sheep, can cost up to 3,000 euro.”

Playing Krampus

What was once Markus’ own childhood fancy has become a veritable boom across Austria. Krampus and Perchta processions have been incredibly popular for about 15 years, with some towns even organizing entire Krampus shows. The Internet and social media have taken the tradition all the way to China, Mexico and the United States. “Obviously, it’s less about tradition and more about the sheer joy of frightening people,” he muses.

When we ask the Innsbruck native what it feels like to join the procession as Krampus, he smiles. The early years, he says, were exciting and really special. “Especially as a teenager, it feels great – after all, there’s lots of girls watching,” he explains. But the excitement has died down by now, and he is critical of some recent developments. A lot of it is about money and partying, rather than tradition, these days. “But that’s just how it goes,” he says. He is determined to keep the “real” tradition alive for the next generation. For a few years, he has been dressing up as Krampus and roaming the streets with his twelve-year-old son, who is doubtlessly just as excited as his dad used to be, back in the day.